Description of Vessel

Statements describing the vessel's gross and/or net register, the deadweight and cubic capacity, and speed and class are included in charters. The registered tonnage does not indicate the vessel's carrying capacity and, unless a large discrepancy is involved, a misstatement regarding the tonnage does not justify rejection of the vessel. Statements regarding deadweight, cubic capacity, speed and class, however, are of great importance to the charterer; such items, when 'guaranteed', are frequently considered as both conditions precedent and warranties permitting the charterer to either reject the vessel or accept it and subsequently sue for damages. Where a vessel's deadweight capacity is guaranteed, however, the guarantee does not mean that the vessel will be able to carry that amount of tonnage with respect to the cargo, even if a particular cargo has been contemplated by the parties. This rule is probably derived from the fact that there is frequently a discrepancy between a cargo's deadweight and its cubic displacement. Where deadweight, capacity, speed and class are not guaranteed, the owner will not be held liable in the absence of a showing of bad faith or fraud.

A guaranty of speed is a continuing one that begins at the time of delivery. Depending on the circumstances and the provisions of the charter, the owner's breach of the guaranteed speed may entitle the charter to damages, e.g., in the form of a reduction or adjustment in hire, reimbursement for extra fuel consumed, or recovery for cargo damages.

The use of the qualification 'about' referring to a vessel's speed has been construed as justifying a deduction of ½ knot from the speed guaranteed, while the deletion of the word 'about' from a printed form has been construed as intending to make precise the speed and bunker representations. In the face of adverse winds and currents the description of a vessel's speed has been held not to constitute an absolute warranty.

Cases dealing with the statement of a vessel's class have been limited to those involving voyage charters. A class warranty is not continuing one like the speed warranty and is satisfied if the vessel is of the class stated at the time of charter was made. Under the usual time charter form, however, the owner would probably be obliged to restore the vessel to her class if she lost it as a result of an accident.

If statements regarding the vessel have been made orally but are not included in the charter, the patrol evidence rule would prevent the charterer from relying on such statements in an action against the owner. He could, however, refuse to perform the charter if he relied on a material misstatement by the owner that would have permitted him to cancel the charter if it had been incorporated into the charter. In England, an owner can be held responsible for his mistaken oral statement regarding a vessel's carrying capacity on the grounds of a breach of a collateral oral warranty.

Recent arbitration decisions have dealt with the problems arising from discrepancies between actual conditions and the charter's description of the vessel's available loading space and dimensions, gear and appurtenances, and cleanliness.

Charterers wishing to guard against extra costs incurred as the result of the vessel's failure to meet agreed standards of fitting and stowage should insure that non-compliance clauses are inserted in the charter party.

Period of Charter: Overlap and Underlap

The usual form of time charter contains a clause in which the charterer agrees to let, and the owner to hire, the vessel for a specific period of time after her delivery. The word 'about' is frequently used to qualify the period of hire. Related to this clause is another provision, generally inserted elsewhere in the charter, which provides that hire shall continue, unless the vessel is lost, until the time of her redelivery at the designated port. Such clauses frequently include the additional requirement that the vessel be redelivered with clean swept holds.

The courts have recognized that redelivery on the specified day is often impracticable considering the exigencies of the maritime industry; consequently, leeway has been given to the charterer concerning redelivery, whether or not the charter includes the 'about' qualification. The expressions 'overlap' and 'underlap' are the relevant terms of art relating, respectively, to the return of the vessel after or prior to the agreed flat period.

The charter provided for a period of three months from time of delivery, without the inclusion of the word 'about' in an early decision dealing with the issue of overlap. During the voyage the vessel's discharging has been greatly delayed by wash-outs and other accidents not attributable to the charterer. As a result, the flat period expired before the vessel completed loading her return cargo. Nevertheless, the loading was completed under the charterer's orders and the vessel eventually redelivered nearly three months after the expiration of the flat period. The subsequent increase in charter rates induced the owner to seek recovery of the difference between the market rate and the charter rate for the extra use of the vessel.

The court held, however, that because of the contingencies of navigation, the parties must have understood that redelivery on a day certain was sent by the charterer was reasonable; there was no breach of the charter.

In another case involving a charter that included an unqualified flat period, the vessel was discharged in Philadelphia thirteen days before expiration of the charter which provided for redelivery at a port north of Hatteras. At that point the charterers wanted to send the vessel on one more voyage to Mexico but the owners refused. The court held that the charterers were entitled to order the vessel to an additional destination, even if an overlap were a certainty, but the trip had to be limited to the shortest voyage contemplated under the charter, which in this case was Cuba.

In later cases involving charter terms qualified by the word 'about', it was decided that the charterer could either overlap or underlap, whichever would bring the period of redelivery nearest the flat period. Meanwhile, in England it has been held that, unless the word 'about' is used; the charterer may overlap but cannot underlap.

In The Rygya the court was faced with the problem of calculating the commencement date of the optional renewal term under a charter providing for an initial period of 'about six months'. It was held that the second period did not begin until the completion of the last voyage undertaken in the first period, even though such voyage ran some seven weeks beyond the end of the first flat period.

After the expiration of the charter period it is settled that the charterer has no right to begin another voyage. In Munson S.S. Line v. Elswick, S.S. Co., it was held that where the flat period expired while the vessel was in a port other than the redelivery port the shipowner had the option to withdraw the vessel rather than allow redelivery. This is also the rule in England. Of course, such privilege need to be exercised, and the owner may require redelivery at a redelivery port even if the vessel must be sent there in ballast.

A variation of the 'about' form of provision was passed upon in an English case where the charter party reduced the 'about' period to a fixed period, i.e., 'until 15/31 October,' and similarly limited the 'hire to continue' clause. It was held that the charterer breached the charter by sending the vessel on a voyage while she was in a port of redelivery on October 18 and such extra voyage was not concluded until November 30, as a result the charterer was required to pay hire at the market rate for the period after October 31.

In a similar manner, many modern charters attempt to limit the 'about' period by employing language such as 'for about two years, two weeks more or less,' thereby clearly defining the 'about' period as extending from two weeks before until two weeks after the flat period. Utilization of such a flexible four-week period is at the charterer's option, and he is not under an obligation to fix the period by specific note.

A recent English decision has indicated, however, that stipulated grace periods are not always effective. The court there held that the fact that unanticipated intervening circumstances result in redelivery of the vessel after the grace period does not allow the owner to demand payment of hire at the market rate rather than at the charter rate if at the time the last voyage is undertaken it appears that it can be completed within the grace period. It should be noted, though, that a 1972 arbitration decision held that 'under some circumstances even an unexpected large overlap becomes unreasonable' and 'the burden should not be borne entirely by the owner.'

Sometimes a time charter provides that time when the vessel is off-hire should be added to the term, frequently at the option of the charterer.

The duration of the charter is normally computed by calculating the difference between the local time at the delivery port and the local time at the redelivery port. A recent decision has held, however, that is 'anachronistic' to employ a method using 'the local time at both ends as a hit-or-miss averaging system' and found in favor of the charterer who had calculated the payment of hire on the basis of Pacific Standard Time.

Seaworthiness

The absolute warranty of seaworthiness formerly implied in charter parties by the general maritime law has been replaced in most modern charters by language requiring the owner to use due diligence to make the ship seaworthy. Under American decisions there is also an implied warranty under most time charters that the vessel is seaworthy at the commencement of each voyage undertaken under the charter.

The undertaking of seaworthiness, however, has not been generally considered a condition precedent of the charter, and a breach thereof will not warrant repudiation unless it is 'so substantial as to defeat or frustrate the commercial purpose of the charter.'

The general test of seaworthiness requires that the vessel by reasonably fit for intended service. However, the question of seaworthiness in charter parties applies not only to the general requirements that the vessel be tight, staunch, strong and fit but in addition the vessel must be fit for the particular cargo the owner has contracted to carry. In Sylvia, Justice Gray clearly stated this point: 'The test of seaworthiness is whether the vessel is reasonably fit to carry the cargo which she has undertaken to transport.' This is the commonly accepted definition of seaworthiness. As seaworthiness depends not only upon the vessel being staunch and fit to meet the perils of the sea, but upon its character in reference to the particular cargo to be transported, it follows that a vessel must be able to transport the cargo which it held out as fit to carry, or it is not seaworthy in that respect.

The seaworthiness of the ship is under the master's absolute control. It is often the case under a time charter that the owner agrees to maintain the ship in a thoroughly efficient state in hull and machinery during the service and the failure to meet this obligation is grounds for an action by the charterer.

A charter may contain provisions placing some of the duty or expense of making the vessel seaworthy on the charterer.

In the New York Produce Exchange form under clause 2 the charterer must furnish dunnage and shifting boards, and any extra fittings required for a special trade or unusual cargo. And under clause 22 the charterer may be responsible for the expenses of the vessel's acquiring heavy duty derricks or for supplying any additional lights.'

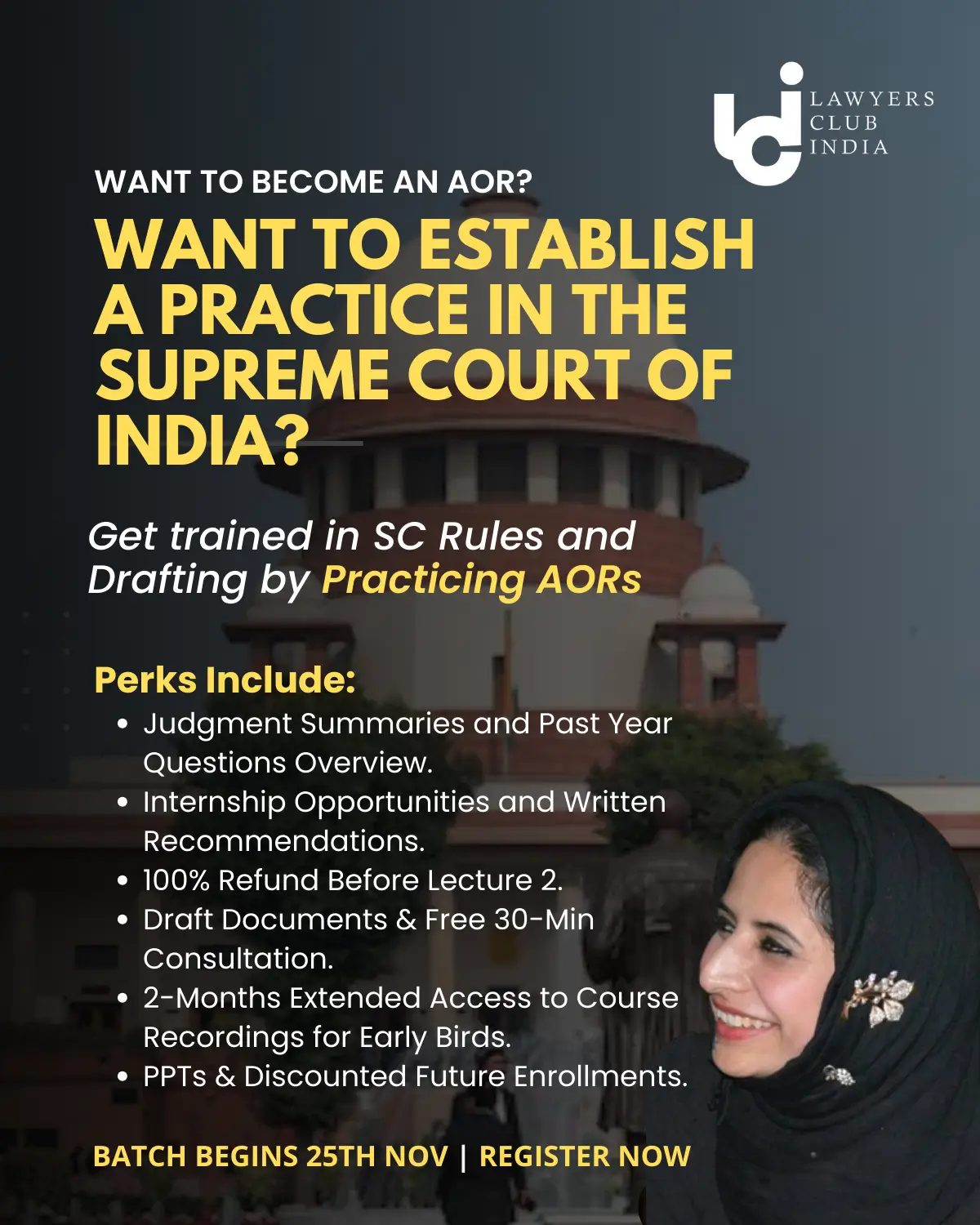

Join LAWyersClubIndia's network for daily News Updates, Judgment Summaries, Articles, Forum Threads, Online Law Courses, and MUCH MORE!!"

Tags :Others