Contempt - is it being stretched too far?

The law relating to contempt of courts is once again in focus. The triggering off contempt proceedings on a senior Advocate of Madras High court has exposed the tautness between the need to preserve public confidence on judiciary and the right to freedom of expression. The description of these words - causing injustice to litigants as 'contempt of court' is in my view unfortunate. The power of contempt clearly protects the court, but what has always, and even more so today, remained ambiguous is what exactly it aims to protect. Lord Diplock who made many contributions to legal thought and pushed the law in new and unique directions said - The due administration of justice requires first that all citizens should have unhindered access to the constitutionally established courts of the criminal or civil jurisdiction for the determination of disputes as to their legal rights and liabilities; secondly, that they should be able to rely upon obtaining in the courts the judgment which is free from bias against any party and whose decisions will be based upon those facts only that have been proved in evidence adduced before it in accordance with the procedure adopted in courts of law; and thirdly that, once the dispute has been submitted to a court of law, they should be able to rely upon there being no usurpation by any other person of the function of that court to decide it according to law. Conduct which is calculated to prejudice any of these three requirements or to undermine the public confidence amounts to contempt of court. The right to be heard is a fundamental protection to Advocates representing the litigants that should not be lost in any circumstances.

Everyone has the right to freedom of expression, including the freedom to seek, receive, and impart information and opinions of any kind in any form. It is axiomatic that an Advocate representing a party to a proceeding, or a potential party to a proceeding, in any court of law is entitled to expect that the proceeding will be determined according to law; and that the law will be duly and justly administered without undue interference. Judges gain respect by remaining impartial and not through contempt proceedings. Fair and reasonable criticism of public institutions, including the judiciary, is a normal part of democratic process when people's liberties are assured by the constitution.

A Judge should learn to ignore as long as his conscience was clear. Justice is not 'a cloistered virtue', said Lord Atkin, and must suffer the scrutiny and outspoken comments of ordinary men. In fact exposure to criticism only strengthens the judiciary, far from weakening it. As observed by Lord Denning in R vs. Commissioner of Police - Let me say at once that we will never use this jurisdiction as a means to uphold our own dignity. That must rest on surer foundations. Nor will we use it to suppress those who speak against us. We do not fear criticism, nor do we resent it. For there is something far more important at stake. It is no less than freedom of speech itself. It is the right of every man, in Parliament or out of it, in the press or over the broadcast, to make fair comment, even outspoken comment, on matters of public interest.

Let me quote from "CONTEMPT OF COURT: THE NEED FOR A FRESH LOOK" By Justice Markandey Katju - The best shield and armor of a Judge is his reputation of integrity, impartiality, and learning. An upright Judge will hardly ever need to use the contempt power in his judicial career. It is only in a very rare and extreme case that this power will need to be exercised, and that, too only to enable the Judge to function, not to maintain his dignity or majesty. In a democracy, on the other hand, it is the people who are supreme, and therefore they are the superior entity, while all State authorities (including Judges) are inferior entities, being the servants of the people.

Once this concept of popular sovereignty is kept firmly in mind, it becomes obvious that the people of India are the masters and all authorities (including the courts) are their servants. Surely, the master has the right to criticise the servant if the servant does not act or behave properly. It would logically follow that in a democracy the people have the right to criticise judges. Hence in a democracy there is no need for Judges to vindicate their authority or display majesty or pomp.

Their authority will come from the public confidence, and this in turn will be an outcome of their own conduct, their integrity, impartiality, learning and simplicity. No other vindication is required in a democracy by Judges, and there is no need for them to display majesty and authority. Power of judiciary lies not in deciding cases, nor in imposing sentences, nor in punishing for contempt, but in the trust, confidence and faith in the common man. Only the judiciary, of its own accord, can make the move towards a more liberal interpretation of contempt that allows healthy criticism that can aid its own development as an institution. Protecting the judiciary as an institution is important. Therefore the law should seek to protect the court as an institution, while a judge as an individual could be open to criticism. However, willful disobedience of the court in any manner that lowers the authority of the court or interferes with or obstructs administration of justice must be checked.

By: K.SURESH BABU

ADVOCATE,9,RAJA COLONY,

SECOND MAIN ROAD,

LAWSONS -COLLECTORS OFFICE ROAD,

CANTONMENT,TRICHY-620001

Email: lawyersureshbabu@gmail.com

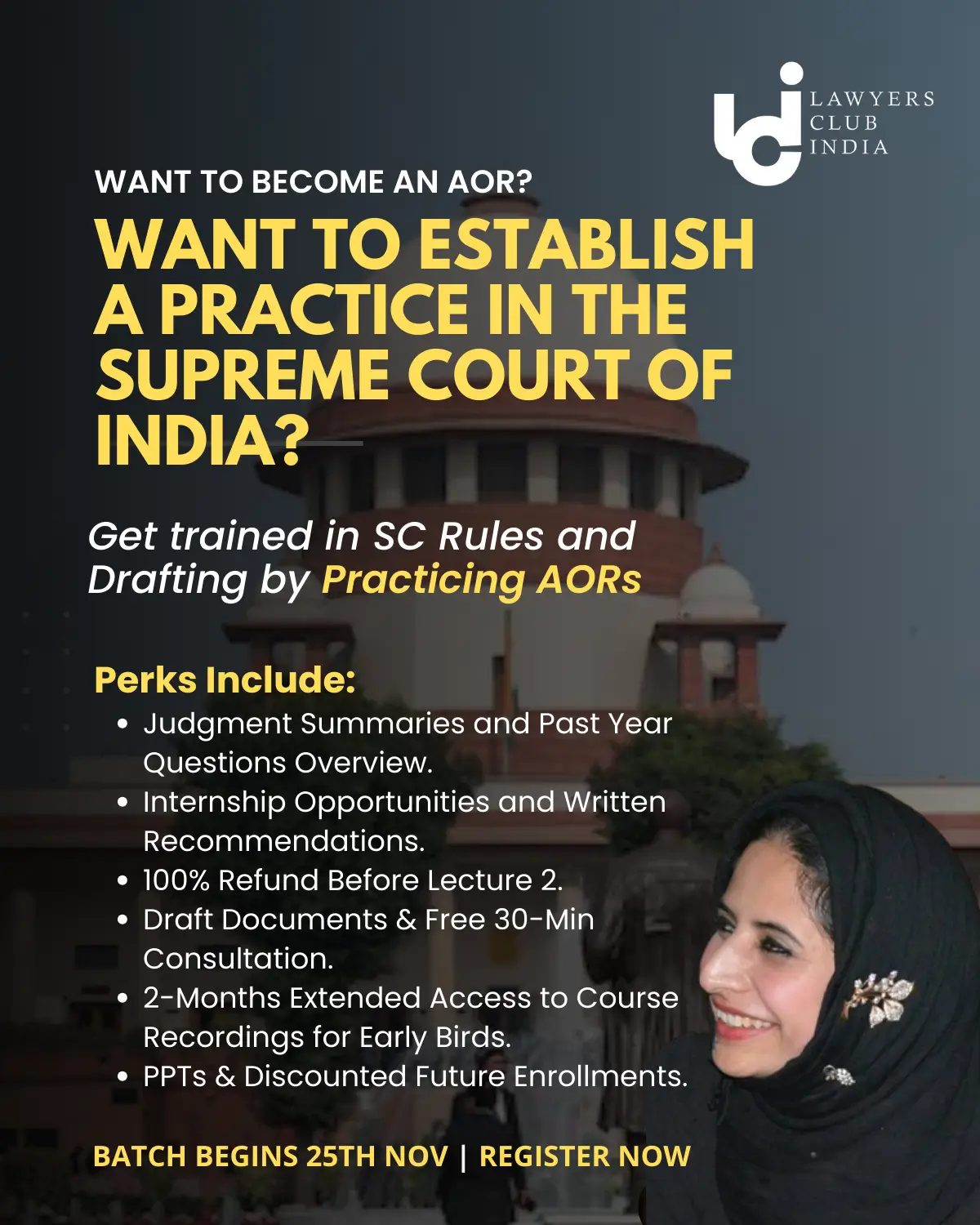

Join LAWyersClubIndia's network for daily News Updates, Judgment Summaries, Articles, Forum Threads, Online Law Courses, and MUCH MORE!!"

Tags :Others