By their very description in the Copyright Act, 1957, cinematograph films are not “original works”, and hence may be categorised as derivative works/adaptations/ user generated content (UGC). The importance of music in films may be gauged from the fact that there is a distinct exclusive right for making and authorising the making of a cinematograph film in respect of the musical work, in addition to a general right of reproduction of the musical work in any medium.

In the absence of a contract to the contrary, the Supreme Court has held that the producer of a film is also the owner of the musical work as embodied in the soundtrack of the film. However, the question of ownership and hence the right to take action in case the same music is used out of context of the soundtrack of the film and where no written agreement exists in respect thereof (or in any case, such out of context rights are not properly addressed in the agreement) is an area where the same court was undecided, leaving the field open for various potential plaintiffs to take action against third parties’ attempt to use film music to generate content. Given that over 80% of all music is film music, the lack of clarity among possible stakeholders, all claiming themselves as owners of the “publishing rights”, ensuing from the aforesaid 30-year-old decision has contributed to the growth of unlicensed UGC, which has, till recently thrived on the aforesaid confusion which shifted the focus from whether the generation of content by the user is actionable, to who can raise such a question. Where claimants could be identified clearly, they were, till very recently, not interested in taking action as they were either not aware of their rights vis-à-vis UGC, or were not bothered once the work was made, incorporated in a film and the film released. A major beneficiary of the aforesaid lack of clarity of ownership has been the version recording industry. Leading the pack (though it today also has the largest original content repertoire), is a company which has, interestingly, sued YouTube in November 2007. While courts entertaining lawsuits against version recordings are yet to give a definitive verdict on whether the fair use provision protecting the making and sale of version recordings mandates consent of the owner of copyright prior to making the version recording, what has further aided the version recording industry is the fact that the plaintiff cannot claim infringement of the record companies’ right to reproduce the sound recording, since Section 2(m) read with Section 14(e) of the Copyright Act only sanctions the embodiment of the original sound recording into another sound recording and not a sound alike sound recording that may have been created afresh. In order to take action against version recordings, the plaintiff has to rely upon the theory of infringement of copyright in the underlying musical and literary works and a breach of the conditions of the fair use provision specifically protecting version recordings. The continued generation and exploitation of UGC in India, as anywhere else, is also attributable to the costs of creation and/or acquisition of original content, which is increasingly hitting the budget allocations, especially in the television industry. Wouldn’t it be more convenient, ask television executives, if a part of the content could be “generated” by mixing existing content? The answer to this question necessarily flows from another question of how much is to be taken, because what is actionable is taking not only the entire work but even a substantial part thereof. Once the taking is judged to be substantial, we step into the domain of fair use/fair dealing to determine whether such substantial taking is protected by principles of fair use. Two pending suits before the Delhi High Court will soon decide the amplitude of fair use in relation to copyrighted works where parts of an existing work are used in news or commentaries on current events/trends, including how much use is substantial enough to be labelled as infringement. Another issue that is likely to arise as more UGC is generated by individuals, but “facilitated” by third parties, is that of contributory infringement. The relative lack of authority on this issue makes it difficult to forecast the landscape that is likely to emerge, but the content owners are likely to have a tough time convincing courts on a contributory infringement theory, especially when they are unwilling to take action against the direct infringers, who may also be customers of such content owners. This is because, in addition to not having provisions introduced by DMCA in the US Copyright Act, the current language of the Copyright Act that defines an infringement only addresses direct infringement and the only aspect of contributory infringement that is included pertains to permitting a public place to be used for communication to the public of a work, where the communication to the public itself is an infringement of copyright. Even in such a case, it is essential to prove that the person giving permission has knowledge that the communication to the public is an infringing use. On the basis of the foregoing, the only conclusion is that as with other issues of copyright law that are in need of clarification, we are likely to witness hectic activity very soon in determination of legality and hence continued feasibility of user generated content.

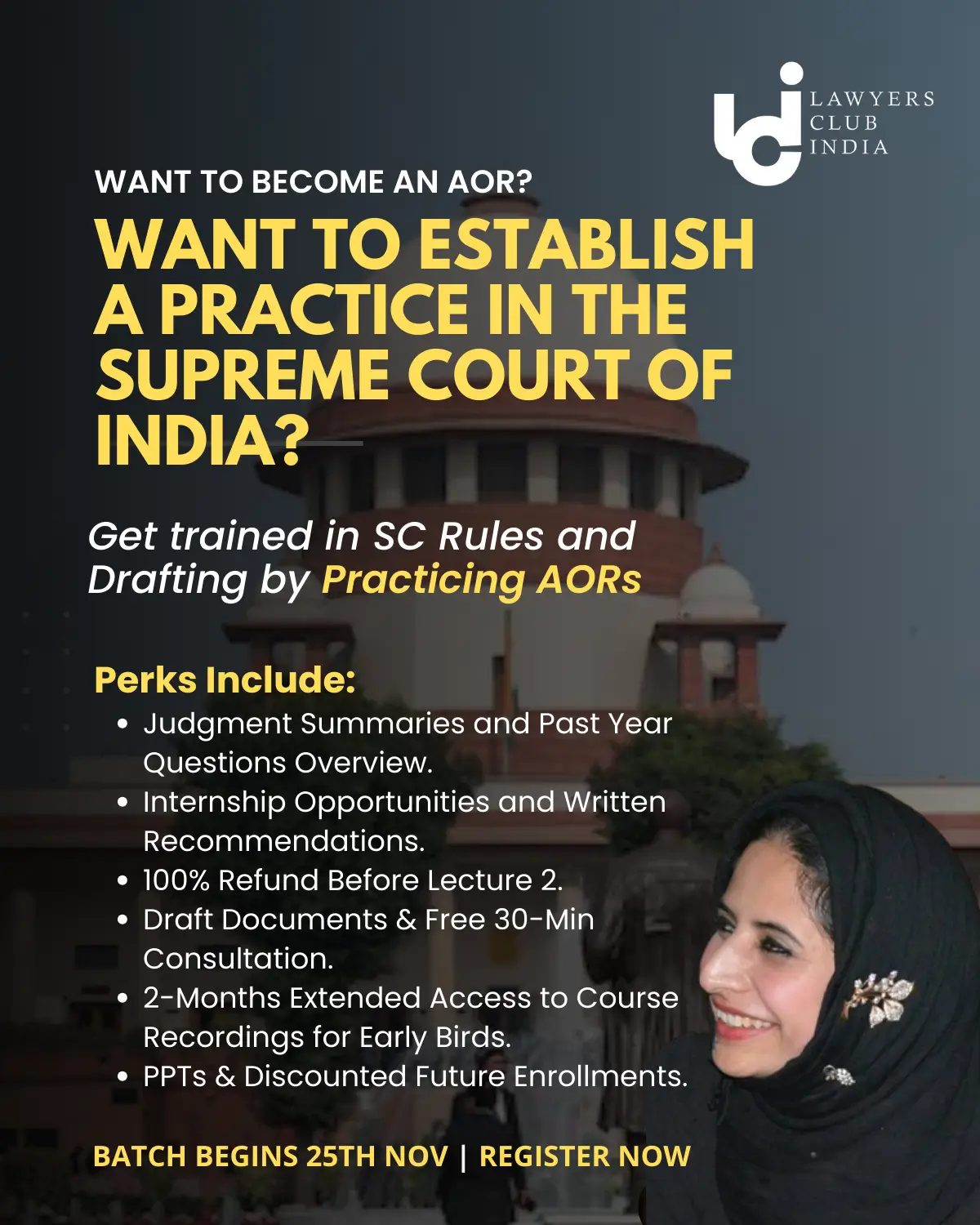

Join LAWyersClubIndia's network for daily News Updates, Judgment Summaries, Articles, Forum Threads, Online Law Courses, and MUCH MORE!!"

Tags :Intellectual Property Rights