With inter-state relations getting increasingly focused on integration, the impetus for summits and meetings has been on the increase.

However, there is also the resounding feeling that these are becoming more rhetorical than real. Almost every month we hear of a summit or a meeting of states, but the actual progress towards resolution of issues and problems in inter-state relations has been less effective and focused. This was clearly evident in the recently-concluded Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) summit, from October 23 to 25, 2009.

The 15th Asean summit took place at Cha-am, Hua Hin in Thailand where Thailand passed on the one-year chairmanship to Vietnam. This summit was important as it was the first meeting to be held after the Asean charter was endorsed in February 2009 also in Hua Hin. Apart from endorsing the Asean charter among the member countries, the February meeting also heralded a shift in Asean functioning — from an informal association of regional states to a more formal structure.

Asean, since its inception in 1967, has had an informal approach where decision-making on key issues of regional concern has been based on a mechanism of collective decision-making. This approach combined the two pillars of "mufakat" and "musyawarah", which mean consensus and consultation respectively. This approach was distinct from other regional or inter-state organisations most of whom have a legal approach to decision-making. Another aspect of this informal approach of the Asean was that it precluded internal domestic affairs from being discussed among the states. As a result, the manner in which the organisation dealt with domestic politics issues remained ambiguous.

Issues relating to human rights were especially considered sensitive. In fact, under the guise of a regionally-distinct approach these were pushed aside as being different for various countries, and claims of an "Asean way" were effectively used to deal with any criticism on matters relating to human rights within the region.

The Asean, therefore, pushed forward the logic that human rights was not a universal principal but distinct for different countries based on their political development and systems. The Asean region, which comprised few liberal democracies, found resonance in the "Asean way" and used this to deflect critical views on issues of democracy and human rights.

Often the countries that did not follow policies of good governance to achieve domestic stability and nation building where not brought to censure. This was particularly evident in the case of Burma where the ruling military junta has not been held accountable. Both in the case of the monk's rebellion of September 2007 and the subsequent referendum during the aftermath of cyclone Nargis, the junta's excesses, apart from a perfunctory rhetorical mention have been overlooked by the Asean.

This approach using informal consensus as a decision-making tool underwent a shift with the 2003 Bali Concord II and the subsequent Vientienne Action Plan which was to construct an Asean similar to the European Union with a more legal framework for managing inter-state relations founded on a rational rule-based formula. This looked towards building three pillars — the Asean security community, the Asean economic community and the Asean socio-cultural community. Integral to this was the Asean Charter in which the rules of engagement would be clearly articulated. One of the pivots of this approach was to focus on issues of democracy and human rights, a clear departure from the manner in which Asean functioned for the first 40 years.

The latest summit in Cha-am, Hua Hin, has come under flak for its inability to give more grit to the Asean Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights (AICHR), which was to be a huge step forward for the Asean. This was to give the charter the much needed legal framework and finalise a set of principles by which Asean member states would be held accountable for human rights violations.

While critics of the Asean human rights approach claim that the provisions lack the ability to deal with these issues, Asean defenders state that this still falls within the purview of the "Asean way". In fact, both the Asean Charter and the terms of reference that bind the AICHR are very vague in their description of human rights violations. They merely talks about non-discrimination, the rights of migrant workers and issues relating to human trafficking. The current status of the terms of reference does not reflect any clear-cut process by which the commission will monitor violations in individual Asean countries. Neither does it have provisions to actually take up individual cases of citizens who may have been victims of human rights excesses. It also remains vague on the appointment of commissioners and what is expected in their selection. In fact, one of the loopholes in the appointments is that it consists of government level appointees. This itself causes a degree of complicity in the functioning of the commission. Many human rights groups have wondered if the commission can behave in a non-partisan manner.

As is evident in the Asian context, there are several ethnic communities and religious minorities that make up the nation state within state boundaries. In an era when there is a growing need for recognition and accommodation within national norms and institutions, the Asean approach to human rights is bound to cause fissures within multilateral institutions such as the East Asia Summit and the Asean Regional Forum. There is a likelihood that one will see a conflict between distinct versions of norms of approach followed within multilateral institutions. China and Asean are likely to follow a more external oriented approach, where the focus will remain on issues of sovereignty and that domestic matters are above the purview of inter-state relations.

On the other hand, the western members are likely to bring a greater emphasis on issues of governance and human rights too. This contradiction in approaches among the members will highlight more clearly the contradiction of norms that are considered universal in principal, rather than being diverse for individual countries. In fact, by endorsing such a weak policy towards human rights, Asean states are once again sending a signal that it remains merely a notional understanding, rather than an effective measure, to counter states which are guilty of human rights violations.

Dr Shankari Sundararaman is anassociate professor ofSoutheast Asian Studiesat the School of International Studies, JNU

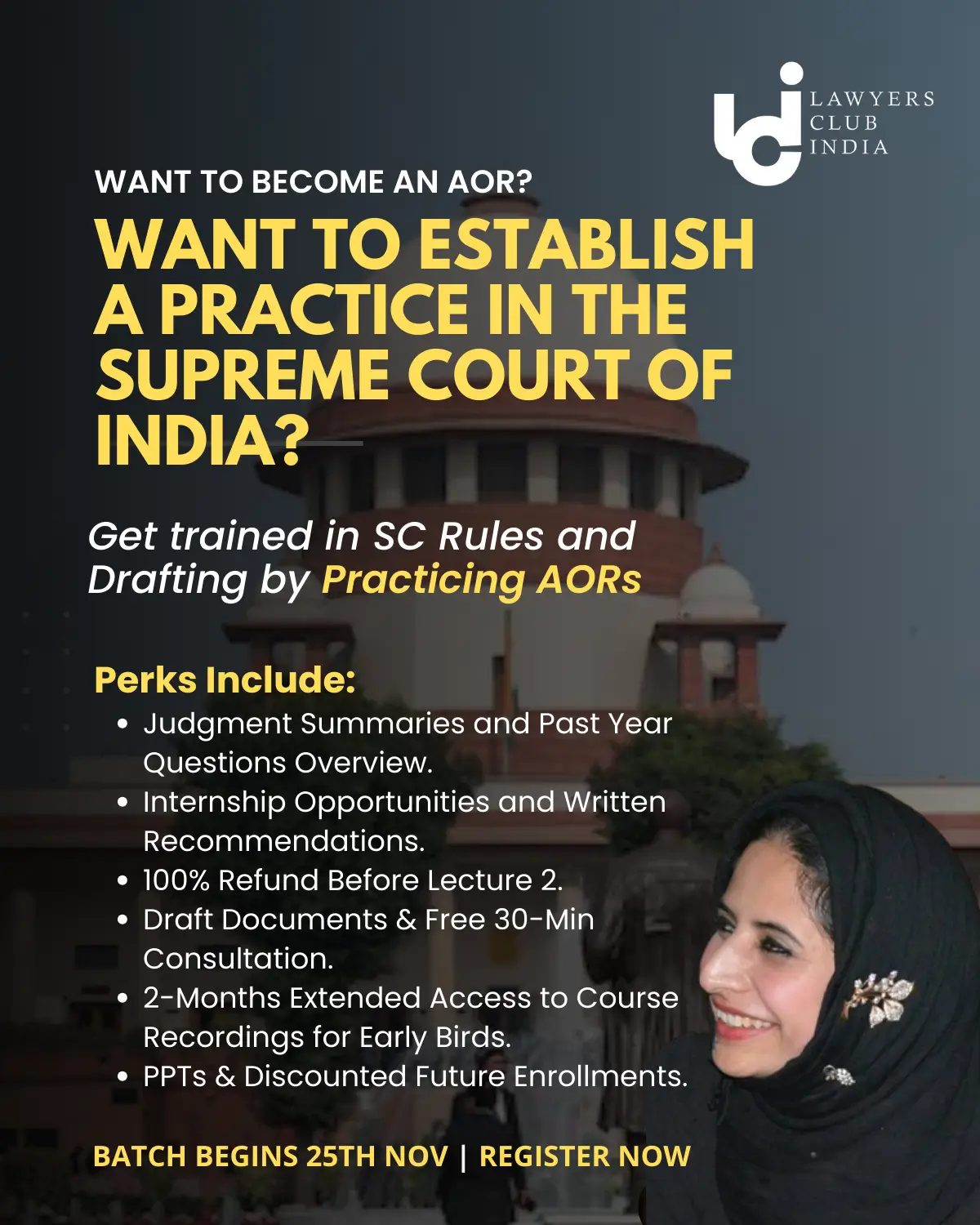

Join LAWyersClubIndia's network for daily News Updates, Judgment Summaries, Articles, Forum Threads, Online Law Courses, and MUCH MORE!!"

Tags :Intellectual Property Rights