Index

- Introduction

- Historical Development of Suicide Laws in India

- Shift from Criminalization to Decriminalization

- Assisted Suicide and Euthanasia

- Judicial Precedents

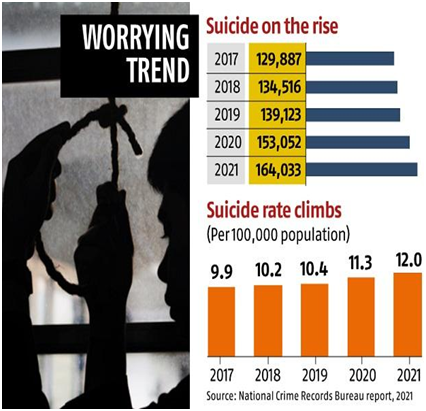

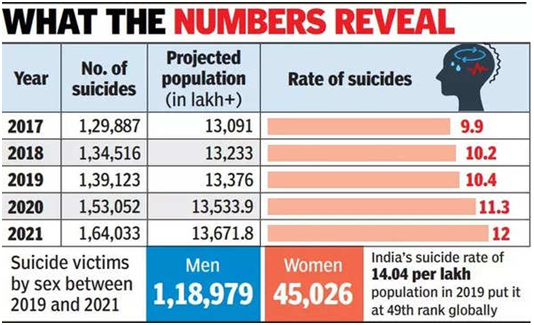

- Statistical Information on Suicide in India

- Conclusion

Synopsis

The legal treatment of suicide has undergone a profound transformation in India, shifting from a punitive approach under colonial-era laws to a more humane and medicalized framework. The criminalization of attempted suicide under Section 309 of the Indian Penal Code was widely criticized for its insensitivity towards individuals suffering from extreme psychological distress. The Mental Healthcare Act, 2017, and the subsequent introduction of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita in 2023 marked a turning point by effectively decriminalizing attempted suicide and prioritizing mental health interventions.

However, while individual suicide is no longer a crime, the legal framework remains stringent on assisted suicide and euthanasia. Provisions under the BNS criminalize the abetment of suicide, particularly in cases involving vulnerable individuals. Meanwhile, euthanasia laws remain nuanced-passive euthanasia has been legalized under strict conditions following the landmark Aruna Shanbaug case, while active euthanasia continues to be prohibited. The judicial landscape surrounding suicide laws has been shaped by significant precedents, including Gian Kaur v. State of Punjab, which upheld the constitutionality of penal provisions against abetment of suicide, and Aruna Shanbaug v. Union of India, which established legal grounds for passive euthanasia.

Statistical analyses indicate a concerning rise in suicide rates in India, particularly among daily wage workers, students, and unemployed individuals, underscoring the need for comprehensive mental health and socio-economic interventions. The evolving legal stance on suicide reflects a broader societal shift toward understanding mental health as a fundamental aspect of human rights while balancing legal constraints against potential misuse of assisted suicide and euthanasia.

Introduction

Suicide has been legally, ethically, and philosophically controversial for centuries, and its legal treatment differs among jurisdictions and across time. Self-killing has been understood in a range of ways-anywhere from a criminal act to an individual choice that is associated with mental illness and human rights.

The Indian laws surrounding the suicide act have radically altered from colonial, retributive legislation to a kinder and medicalized regime, understanding the psychiatric anguish of attempted suicide. Still, beyond the act of decriminalization itself, the suicide law also concerns more complex issues such as assisted suicide, euthanasia, and the moral challenges of the right to die. A glance at India's legal response in relation to international practices provides us with an insight into the evolving attitude towards suicide and its juridical, public policy, and social implications.

Historical Development of Suicide Laws in India and the Shift from Criminalization to Decriminalization

Indian suicide response derives its origin in the colonial era, with laws during the British period having influenced much of the country's legal structure. Under Section 309 of the Indian Penal Code, attempted suicide had been criminalized as an offence for which attempters could face punishment of a maximum one year imprisonment, or fine, or both for the would-be suicides but survivors. The justification of this provision rested on a variety of considerations, including the perspective that suicide was legally and morally bad, bad against the state, and contrary to religious and social values. Criminalizing attempt at suicide also acted as a deterrent to discourage people from trying to commit suicide. However, legal brains, physicians, and mental health clinicians criticized Section 309 in later years for being humane in the way it condemned suicide attempters as victims of extreme psychological illness and required instead of punishment the provision of medical care.

Master Our Practical Course on "Indian Penal Code" for Young Lawyers. Click here to enroll now!

The Mental Healthcare Act, 2017 was the first landmark move towards decriminalizing suicide. It was a revolution in the way India was handling suicide and mental illness. The Act, through Section 115, assumed that all the people who tried to commit suicide were under severe stress and did not deserve to be prosecuted under criminal law. Instead, the legislation provided that such individuals should be given proper mental healthcare treatment and counseling. This clause practically made Section 309 of the IPC ineffective in most instances, recognizing that criminalizing attempt at suicide did nothing but extend the suffering of vulnerable individuals. The introduction of the BNS in 2023, in place of the IPC, further solidified this change by having no provision for criminalizing attempted suicide, and thereby de facto decriminalizing it in India. This modification is a wiser and more compassionate response to suicide, keeping Indian law aligned with best international practices for mental illness treatment and suicide prevention.

Assisted Suicide and Euthanasia

Though attempted suicide has been de-criminalized, the position of law for assisted suicide-is where one person helps or prompts another to suicide-is still problematic in India. In contrast with most Western countries that have grappled with or legalized doctor-assisted suicide in limited cases, India continues to prohibit assisted suicide under Section 305 and Section 306 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, the law criminalizing abetment of suicide.Such provisions include cases when the individual is being induced, coerced, or assisted in committing suicide with increased penalties in cases where the individuals involved belong to vulnerable groups such as children, mentally unstable, or dependents. Such laws are justified to prevent potential abuse, pressure, or compulsion that can lead to people taking their own lives under force.

The controversy of euthanasia, or the active termination of life to cause death to stop suffering, only adds to the legal complication of the debate over suicide. Although active euthanasia, in which one does so intentionally to give the fatal dose in order to end the life of the patient is illegal in India, passive euthanasia, in which treatment to sustain oneself in alive state is not given in the event of terminal illness or permanent disease is legal under strict conditions in the case of Aruna Shanbaug v. Union of India.

The Supreme Court, in this verdict, identified the right to die with dignity as a correlative of Article 21 of the Indian Constitution that grants the right to life. The same ruling was reaffirmed in 2018 when the Supreme Court legalized making living wills, by which people could pre-emptively decide what they wanted as regards end-of-life medical interventions.

Such legal progression has provided an equalizing context wherein euthanasia is partly legalized in the form of regulated cases, manifesting an equal measure between preservation of life and individual autonomy respect.

Judicial Precedents

Gian Kaur versus State of PunjabThe Supreme Court contested the constitutionality of Sections 306 and 309 of the IPC in the historic Gian Kaur v. State of Punjab decision. Gian Kaur and her spouse were found guilty under Section 306 of aiding and abetting their daughter-in-law's suicide. On the grounds that Section 309 was unconstitutional, as previously determined in P. Rathinam v. Union of India, they contested their conviction. The P. Rathinam ruling interpreted the right to die as a component of the right to life under Article 21 of the Constitution, thus declaring Section 309 unconstitutional.

Therefore, Section 306 should also be declared unconstitutional. But the five-judge bench in Gian Kaur overruled P. Rathinam, who believes the right to life does not necessarily encompass the right to die. The Court concluded that the right to life is a natural right and antithetical to death, hence that the argument the right to life encompasses the right to die legally is unsustainable.

In Paragraph 24, the Court noted that "the 'right to life' is necessarily inimical to the 'right to die', as death is antithesis to life." Also, in Paragraph 25, the Court specifically held that "Article 21 assures protection of life and liberty of a person and does not encompass the right to terminate one's own life." The ruling preserved the constitutionality of Section 309 IPC, which criminalizes suicide attempts, refuting the belief that one has an untrammelled right to commit suicide.

Aruna Ramachandra Shanbaug vs. Union of IndiaAruna Shanbaug, who worked as a nurse in the KEM Hospital, Mumbai, after having been savagely sexually assaulted and incurring substantial brain injury, had spent nearly 37 years in a continued state of coma. A writ petition had come before the Supreme Court filed by Pinky Virani for a right to permit herself a mercy killing. The Court differentiated between passive and active euthanasia and played a traditional line of defense. The Court itself explicitly declared in Paragraph 101 that "active euthanasia, which is a positive act to kill, is not acceptable under Indian law and would amount to culpable homicide."

Nevertheless, the Court allowed passive euthanasia withdrawal of life support under rigorous conditions. In Paragraph 124, the Court provided clear instructions on passive euthanasia, making removal of life support conditional upon prior sanction by the High Court. The Court ordered that a panel of medical experts be formed to study the patient's condition before a euthanasia decision. Although the petition for granting euthanasia to Aruna Shanbaug was denied, this judgment was a milestone in legalizing the right to die with dignity in India.

Naresh Marotrao Sakhre v. Union of IndiaYet another milestone case with regard to euthanasia was Naresh Marotrao Sakhre v. Union of India, which dealt with the legal status of euthanasia from the perspective of doctors. The petitioner, Dr Naresh Marotrao Sakhre, sought legal interpretation on whether administering a terminal patient a lethal dose of injection as per the request of the patient would amount to culpable homicide.

Bombay High Court categorically decided euthanasia, regardless of the motive, is against Indian law. The Court stated in Paragraph 14 that "intentionally causing death, even with compassionate intent, falls under the purview of culpable homicide under Section 302 of the IPC."

The Court sternly asserted that medical professionals are obligated to savlivesfe and cannot legally participate in terminating the life of a patient. The Court also made it clear that the law on euthanasia cannot be changed by judicial dictum but needs to be altered legislatively.

In Para 16, the Court held that "allowing euthanasia would need a clear legislative intervention since courts cannot make exceptions to current criminal law by way of judicial interpretation." This judgment reasserted the strict legal ban on active euthanasia in India and emphasized legislative reform as necessary if euthanasia was to be legalised.Statistical Information

Suicide Rates in India: A Growing Concern

According to the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) report of 2022, India recorded 164,033 suicides, marking a 6.1% increase from the previous year. This places India's suicide rate at 12 per 100,000 people, a figure that has steadily risen over the past decade.

The following chart illustrates the annual suicide trends in India from 2015 to 2022, showing a significant upward trajectory:

Suicides in India (2015-2022)

|

Year |

Total Suicides |

Suicide Rate (per 100,000) |

|

2015 |

133,623 |

10.6 |

|

2016 |

131,008 |

10.4 |

|

2017 |

129,887 |

10.2 |

|

2018 |

134,516 |

10.5 |

|

2019 |

139,123 |

10.9 |

|

2020 |

153,052 |

11.3 |

|

2021 |

163,536 |

12.0 |

|

2022 |

164,033 |

12.1 |

Analysis:

- The COVID-19 pandemic saw an unprecedented spike in suicides due to financial distress, mental health issues, and isolation.

- The trend shows consistent growth in suicide rates, indicating worsening socio-economic conditions and inadequate mental health support.

Suicide Rates by Profession and GenderBreakdown of Suicides by Profession (2022)

|

Profession |

Number of Suicides |

% of Total Suicides |

|

Daily Wage Workers |

42,004 |

25.6% |

|

Self-Employed |

17,533 |

10.7% |

|

Students |

13,089 |

8.0% |

|

Unemployed |

11,931 |

7.2% |

|

Farmers/Agricultural Workers |

10,881 |

6.6% |

Analysis:

- Daily wage workers account for over one-fourth of all suicides, highlighting the financial insecurities and economic distress faced by this group.

- Student suicides remain alarmingly high, linked to academic pressure, unemployment fears, and mental health challenges.

- Farmer suicides continue to be a persistent issue, largely due to crop failures, debt burdens, and poor government support.

Suicides by Gender (2022)

|

Gender |

Total Suicides |

% Share of Total |

|

Males |

113,666 |

69.3% |

|

Females |

50,067 |

30.5% |

|

Others |

300 |

0.2% |

Analysis

- Males account for nearly 70% of suicides, which may be due to higher financial burdens, social expectations, and lower mental health treatment rates.

- Women's suicides are often linked to domestic violence, dowry harassment, and social stigma surrounding divorce and single motherhood.

- Transgender suicides remain underreported, but marginalization and discrimination play a key role in their mental health crisis.

Laws Regulating Suicide Worldwide

United Kingdom

Suicide was legalized in the United Kingdom by the Suicide Act of 1961, recognizing that those who try to commit suicide should be treated by doctors and not be prosecuted. Assisted suicide is strictly outlawed, however, with an option of punishment by up to 14 years in prison by Section 2 of the Act. The House of Lords ruled in her favor, and the Director of Public Prosecutions published guidelines emphasizing the fact that compassionate assistance is less likely to be pursued.

Although public opinion has shifted with over 75% of Brits supporting the legalization of assisted dying Parliament has repeatedly voted down attempts at legislation to introduce physician-assisted death. The most recent, the Assisted Dying Bill, was defeated on concerns of bullied vulnerable people. Supporters think legalizing assisted dying would bring patients dignity and a choice, while opponents fear that it would push the elderly or disabled to premature death. The UK is still grappling with the ethical dilemma but change is approaching.

United States

There is no federal law with regard to assisted suicide in America, therefore, it falls upon the states.Since Oregon made physician-assisted suicide legal back in 1997 through passing the Death with Dignity Act, a growing number of states have proceeded to follow its example. In general, the law demands that:

- The patient be diagnosed with a terminal condition and prognosis of six months or less to live.

- The request be voluntary, with the mental competency being certified by two doctors.

- The patient undergoes an obligatory waiting time before they receive lethal injection.

Master Our Practical Course on "Indian Penal Code" for Young Lawyers. Click here to enroll now!

Where assisted suicide is legal in these states, euthanasia remains illegal nationwide. One of the other primary criticisms of the U.S. debates is the perceived economic incentives that government programs and insurance companies might have to encourage assisted suicide as an alternative to costly medical care. Critics envision vulnerable populations of individuals, the disabled and elderly in particular, subject to economic or social coercion to cut their lives short.

A 2024 report indicated that since Oregon first legalized assisted suicide, over 8,700 Americans have chosen to do so. The trend indicates growing acceptance of physician-assisted death in America, but adamant opposition remains in most conservative states where laws still criminalize the practice.

Canada

Canada legalised Medical Assistance in Dying in 2016, initially subjecting early eligibility to those with terminal illness and unbearable suffering. Legislative amendments have subsequently, nevertheless, widened access considerably. In 2021, the law of MAID was broadened to encompass patients with non-terminal chronic diseases, and steps are being taken to add the mentally ill by 2027. The rapid spread of MAID has also seen ethical debate on vulnerable persons being presented with death as an easier option than medical and social care.

Critics argue that the substantial increase in assisted suicides is a sign of broader issues with palliative care, mental health, and disability services. Furthermore, there are documented cases in which people have sought for MAID owing to homelessness, financial difficulties, or inadequate medical treatment, raising the question of whether Canada prioritises death over care.

The public, however, continues to favor MAID despite such issues, and Canada continues to widen its framework.

Netherlands

In 2002, the Netherlands became the first country to fully legalise assisted suicide and euthanasia, subject to certain limitations. Under Dutch law, a patient may request euthanasia if there are the following reasons. Euthanasia can be requested by a patient if they:

- Suffer from unbearable, incurable pain with no hope of recovery.

- Give clear, spontaneous consent without coercion.

- Have their case examined by at least two independent doctors.

In contrast to the majority of other nations, the Netherlands does not restrict assisted dying to terminally ill patients; those with severe disabilities, dementia, or chronic mental illness may also qualify.

In 2023, euthanasia killed approximately 9,000 people in the Netherlands, making up almost 5% of total deaths.Often mentioned as an example of both progressive policy and potential damage, the Dutch law is criticised for its extensive implementation, which some claim makes state-sanctioned death the norm.

France

Euthanasia and assisted suicide are still illegal in France, but the nation has been increasingly moving towards legalizing end-of-life decisions under strictly controlled conditions. The Leonetti Law of 2005 legalized "passive euthanasia" by permitting physicians to withdraw life support and provide deep sedation to incurable patients until natural death. The law was expanded by the Claeys-Leonetti Law of 2016 to allow continuous deep sedation until death in incurably suffering patients. However, active euthanasia-in which a physician actually gives a fatal dose-remains illegal.

There has been rising debate about euthanasia in France in the past few years, with President Emmanuel Macron promising to introduce new laws that will legalize assisted dying. At a 2023 citizens' convention of randomly selected citizens, legalizing assisted suicide on tight conditions was advocated very strongly. Opposition by religious circles and physicians, however, has prevented any solid legislative step.

Vincent Lambert, a paraplegic man in a lifelong vegetative state, was one of the most well-known euthanasia instances in France. He finally had his feeding tubes removed after a protracted legal struggle between his family members over whether to discontinue his life support. The case spurred politicians to create more permissive euthanasia rules and fuelled national discussions over the freedom to die with dignity vs the sanctity of life.

Assisted suicide is still illegal until 2024, but new plans show France to be among the leading countries in Europe with more liberal policy adoption. A bill will be presented before Parliament that will provide the way forward for a regime of regulated assisted dying with built-in protection to avoid abuse.

Australia

While assisted suicide and euthanasia have always been illegal in the nation, the Rights of the Terminally Ill Act of 1996 allowed euthanasia in the Northern Territory for a brief period of time before the federal government repealed it in 1997.

Euthanasia was banned nationally for almost two decades.

It all changed in 2017, however, with Victoria leading the charge and the Voluntary Assisted Dying Act 2017 making voluntary assisted dying lawful. The remainder of the Australian states soon after legalized it with Western Australia, Tasmania, South Australia, Queensland, and New South Wales copying the same measure, with the result that assisted dying is a reality throughout Australia.

The Northern Territory and the Australian Capital Territory are not, though, since federal law continues to keep them from legislating euthanasia.

Australia's euthanasia legislation has tight eligibility requirements with the condition that:

- The patient suffer from a terminal illness with less than six months' prognosis (12 months in the case of neurodegenerative conditions).

- The patient be subject to a set of medical tests to ensure voluntary and informed consent.

- Be requested on the patient's behalf, but with coercion prevention measures.

After legalization, euthanasia has grown steadily. Since the law went into effect, more than 600 people in Victoria alone have chosen assisted suicide. Unfair access is a worry, though, particularly in remote areas where physicians might not be able or willing to prescribe death.

Australia's federal Parliament cleared the path for more expansion in 2023 by lifting restrictions that had prevented the ACT and Northern Territory from enacting euthanasia legislation. Australia is now one of the most liberal places for assisted dying, as public opinion spurs continued legislative movement.

ItalyItaly has traditionally been traditional in its perception of euthanasia and assisted suicide, caused by the powerful Catholic heritage in the country. The Italian Penal Code (Article 579) makes active euthanasia and assisted suicide a crime punishable with five to 12 years of imprisonment. There have been judicial decisions and social campaigns in the last few years that started opposing these bans, which opened up the way towards a more advanced legal policy.

One such milestone case was that of Fabiano Antoniani, who was a quadriplegic and sought assisted suicide in Switzerland. His case made headlines across the nation when his right-to-die campaigner Marco Cappato was charged with escorting him. In 2019, Italy's Constitutional Court legalized assisted suicide to a degree under tight parameters in a ruling when it declared that patients experiencing "irreversible suffering" can be offered medical aid in dying if relief is not available otherwise.

Despite such a decision, Parliament has so far not enacted formal legislation about assisted dying, and thus patients are still left in a juridical purgatory wherein assisted suicide is legally permitted but de facto impossible. A euthanasia national referendum was set for 2022 but was voted down by Italy's Constitutional Court as constituting a problem of insufficient safeguard and exploitation.

The Catholic Church remains one of the strongest critics of euthanasia in Italy, arguing that human life is sacred and that the embrace of assisted dying contravenes the palliative care laws. Pope Francis has several times denounced euthanasia as a "defeat for humanity."

Up to 2024, assisted dying continues to plague Italy, with pressure from the public for a better organized legal system. Religious and political opposition, however, remains a major impediment to reform.

Conclusion

India's law on suicide has transformed from a retributive to a humane and rehabilitative one, aligned with global best practices in mental health and human rights. Decriminalization of attempted suicide by the Mental Healthcare Act, 2017, and its reaffirmation in the BNS, 2023, is a major move towards understanding suicide as a mental health emergency rather than a criminal offense. But the legal distinction between suicide, assisted suicide, and euthanasia remains problematic.

Join LAWyersClubIndia's network for daily News Updates, Judgment Summaries, Articles, Forum Threads, Online Law Courses, and MUCH MORE!!"

Tags :Others