INTRODUCTION

Sucession is the transmission of property belonging to a person at his death to some other person or persons.

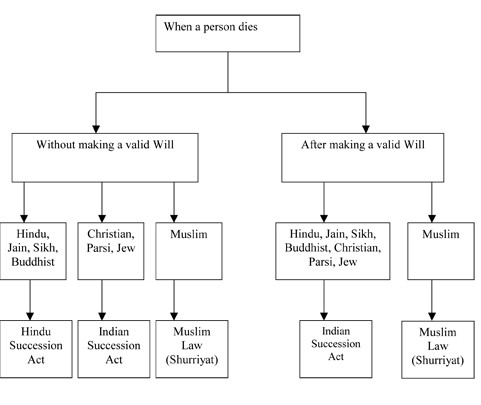

Succession and Inheritance can be of two kinds – Testamentary or testate inheritance which means inheritance as per the Will of the deceased and Non Testamentary or intestate succession, where the deceased dies without making a Will.

The law on intestate succession for different communities in India is governed by different succession laws applicable for that particular community. For e.g. the Hindu Succession Act, Indian Succession Act, Shariat laws etc. The law on testate succession is governed by the Indian Succession Act, 1925 for all communities except Muslims. The law in relation to making of wills by Muslims is governed by the relevant Muslim Shariat Law as applicable to the Shias and the Sunnis.

With the exception of Muslims, the Indian Succession Act, 1925 governs and has a common set of rules for persons of all religions. However, the Muslims shall be bound by the Indian Succession Act, 1925 for the purpose of testamentary succession, if the will relates to immovable property situated within the State of West Bengal and within the jurisdiction of the Madras and Bombay High Courts. Applicability of the Succession law to a person belonging to a particular community is explained in the following diagram:

INDIAN SUCCESSION ACT, 1925

The Indian Succession Act came into operation on 30th September 1925 and it seeks to consolidate all Indian Laws relating to succession. The Act consists of 11 parts, 391 sections and 7 schedules. This Act is applicable to intestate and testamentary succession.

Succession" means capable of comprehending every kind of passing of property. When the British settled down to govern India, they were faced with the task of ascertaining the nature and incidents of the laws to be administered. With reference to the two main communities inhabiting the country, namely, the Hindus and Mohammadans, each of these communities had its own personal laws embodied in its sacred texts, but there were other smaller sections of the population which belonged to neither of these communities and in those cases it was not proper to administer the laws of a religion to which they did not owe any adherence or commitment. Amongst such minor communities were the Christians and Parsis. It was then the thought of enactment of law of succession for the other communities was felt. Thus came the Indian Succession Law.

Consanguinity

Part IV of the Indian Succession Act deals with Consanguinity. This part does not apply to intestate or testamentary succession to the property of any Hindu, Muhammadan, Buddhist, Sikh, Jain or Parsi. Consanguinity is the connection or relation of persons descended from the same stock or common ancestor. Lineal consanguinity is that which subsists between two persons, one of whom is descended in a direct line from the other, as between a man and his father, grandfather and great-grandfather, and so upwards in the direct ascending line; or between a man and his son, grandson, great-grandson and so downwards in the descending line.

Collateral consanguinity is that which subsists between two persons who are descended from the same stock or ancestor, but neither of whom is descended in a direct line from the other.

For the purpose of succession, there is no distinction—

(a) between those who are related to a person deceased through his father, and those who are related to him through his mother; or

(b) between those who are related to a person deceased by the full blood, and those who are related to him by the half blood; or

(c) between those who were actually born in the lifetime of a person deceased, and those who at the date of his death were only conceived in the womb, but who have been subsequently born alive.

Intestate Succession

Part V of the Indian Succession Act deals with Intestate Succession. This part will not apply to the property of any Hindu, Muhammadan, Buddhist, Sikh or Jain. Under the Indian Succession Act, a man’s widow and children, male and female, inherit equally. However, a man may, by Will can bequeath his or her property to anyone, totally disinheriting his own children and widow.

MUSLIM LAW OF SUCCESSION

The Muslim law of succession is a codification of the four sources of Islamic law, which are

(1) The Holy Koran,

(2) The Sunna — that is, the practice of the Prophet,

(3) The Ijma — that is, the consensus of the learned men of the community on what should be the decision on a particular point, and

(4) The Qiya — that is, an analogical deduction of what is right and just in accordance with the good principles laid down by God.

Muslim law recognizes two types of heirs, the first being Sharers, and the second being Residuaries. A relative who is a Sharer will take a specified portion of the deceased's estate irrespective of anything else excepting for one important exception being the Rule of Awl and Radd. A relative who is a Residuary will take whatever is left over, once the Sharers have taken their specified shares.

The Sharers are 12 in number and are as follows:

(1) Husband,

(2) Wife,

(3) Daughter,

(4) Daughter of a son (or son's son or son's son's son and so on),

(5) Father,

(6) Paternal Grandfather,

(7) Mother,

(8) Grandmother on the male line,

(9) Full sister

(10) Consanguine sister

(11) Uterine sister, and

(12) Uterine brother.

The share taken by each sharer will fluctuate in certain circumstances. For instance, a wife takes a one-fourth share in a case where the couple are without lineal descendants, and a one-eighth share otherwise. A husband (in the case of succession to the wife's estate) takes a half share in a case where the couple are without lineal descendants, and a one-fourth share otherwise. A sole daughter takes a half share. Where the deceased has left behind more than one daughter, all daughters jointly take two-thirds. However, these two rules apply only in cases where the deceased has left behind no sons. If the deceased had left behind son(s) and daughter(s), then, the daughters cease to be sharers and become residuaries instead, with the residue being so distributed as to ensure that each son gets double of what each daughter gets. Lineal descendants (such as sons) exclude brothers and sisters, and therefore, the share of brothers and sisters (whether full, consanguine or uterine) will become nil in the presence of such descendants.

Next is the Rule of Awl and Radd. There may be, and indeed there are, cases where the arithmetical sum of the fractional shares to which each Sharer is entitled, becomes more than One. This is not an absurdity. Muslim Law clearly provides for such contingencies as well. In such cases, the ratio of the shares held by each sharer is preserved, crystallized, and reworked out so as to ensure that they succeed to the available estate in that ratio.

There is no concept of ancestral property or rights by birth in the case of Muslim succession. The rights that a Muslim's heirs acquire upon his death are fixed and determined with certainty on that date and do not fluctuate.

Widow’s right to succession

Under Muslim law, no widow is excluded from succession. A childless Muslim widow is entitled to one-fourth of the property of the deceased husband, after meeting his funeral and legal expenses and debts. However, a widow who has children or grandchildren is entitled to one-eighth of the deceased husband's property. If a Muslim man marries during an illness and subsequently dies of that medical condition without brief recovery or consummating the marriage, his widow has no right of inheritance. But if her ailing husband divorces her and afterwards, he dies from that illness, the widow's right to a share of inheritance continues until she remarries.

Legitimacy under Muslim Law

Parentage is only established in the real father and mother of a child, and only if they beget the child in lawful matrimony. In Hanafi Law maternity is established in the case of every child but in Shiite Law, maternity is established only if the child is begotten in lawful wedlock. They (Sunnis or the Hanafis) adopt a view that an illegitimate child, for certain purposes, such as for feeding and nourishment, is related to the mother. For these purposes the Hanafi Law confers some rights on its mother.

In Muslim Law, a son to be legitimate must be the offspring of a man and his wife or that of a man and his slave; any other offspring is the offspring of ‘Zina’, which is illicit connection, and hence is not legitimate. The term 'wife' essentially implies marriage but marriage may be entered into without any ceremony, the existence of marriage therefore in any particular case may be an open question. Direct proof may be available, but if there be no such proof, indirect proof may suffice. Now one of the ways of indirect proof is by an acknowledgement of legitimacy in favour of a son. This acknowledgement must be made in such a way that it shows that the acknowledger meant to accept the other not only as his son, but also as his legitimate son.

Thus under Muslim Law acknowledgement as a son prima facie means acknowledgement as a legitimate son. Therefore, under the Muslim Law there is no rule or process, which confers a status of legitimacy upon children proved to be illegitimate. The Privy Council in Sadiq Hussain v. Hashim Ali pithily laid down this rule:

"No statement made by one man that another (proved to be illegitimate) as his son can make other legitimate, but where no proof of that kind has been given, such a statement or acknowledgement is substantive evidence that the person so acknowledged is the legitimate son of the person who makes the statement, provided his legitimacy is possible."

In Muslim law, the illegitimate child has no right to inherit property through the father and in the classical law, as well as in some modern Islamic jurisdictions, the mother of an illegitimate child may well find herself subject to harsh punishments imposed or inflicted on those found guilty of zina. Thus, the difficult status of legitimacy in Islamic law has very important consequences for children and their parents, especially mothers. Under no school of Muslim law an illegitimate child has any right of inheritance in the property of his putative father.

INHERITANCE UNDER THE HINDU SUCCESSION ACT, 1956

Background

Patrilineal Hindu law is divided into two schools, the Dayabhaga and Mitakshara. Dayabhaga prevails in West Bengal, Assam, Tripura and in most parts of Orissa whereas Mitakshara is followed in the rest of India. Mitakshara law is again divided into Benaras , Mithila, Mayukha (Bombay) and Dravidia (Southern) sub-schools.

One of the important differences between the two schools is that under the Dayabhaga, the father is regarded as the absolute owner of his property whether it is self-acquired or inherited from his ancestors. Mitakshara aw draws a distinction between ancestral property (referred to as joint family property or coparcenary property) and separate (e.g. property inherited from mother) and self-acquired properties. In case of ancestral properties, a son has a right to that property equal to that of his father by the very fact of his birth. The term son includes paternal grandsons and paternal great-grandsons who are referred to as coparceners. An important category of ancestral property is property inherited from one's father, paternal grandfather and paternal great-grand father. The other categories are: i) Share obtained from partition (ii) accretions to joint properties and self-acquisitions thrown into common stock. In case of separate or self-acquired property, the father is an absolute owner under the Mitakshara law.

Under the Mitakshara School, the joint family property devolves by survivorship. When a male Hindu dies after the commencement of this Act having at the time of his death an interest in a Mitakshara coparcenary property, his interest in the property will devolve by survivorship upon the surviving members of the coparcenary and not in accordance with this Act. However if the Mitakshara dies leaving behind a female relative or male relative claiming

through Class I, this undivided interest will not devolve by survivorship but by

succession as provided under the Act.

Applicability of the Act

The Hindu Succession Act applies to:

(a) to any person, who is a Hindu by religion in any of its forms or developments including a Virashaiva, a Lingayat or a follower of the Brahmo, Parathana or Arya Samaj.

(b) to any person who is Buddhist, Jain or Sikh by religion, and

(c) to any other person who is not a Muslim, Christian, Parsi or Jew by religion unless it is proved that any such person would not have been governed by the Hindu law or by custom or usage as part of that law in respect of any of the matters dealt with herein if this Act had not been passed.

The following persons are considered as Hindus, Buddhists, Jains or Sikhs by religion:

(a) any child, legitimate or illegitimate, both of whose parents are Hindus, Buddhists, Jains or Sikhs by religion.

(b) any child, legitimate or illegitimate one of whose parent is a Hindu, Buddhist, Jain or Sikh by religion and who is brought up as a member of the tribe, community, group or family to which such parent belongs or belonged.

(c) any person who has converted or re-converted to the Hindu, Buddhist, Jain or Sikh religion.

General Rules of Succession - Male Hindu

The property of the male Hindu dying intestate will devolve in the following manner:

• Firstly upon all the heirs, being the relatives specified in Class I;

• Secondly, if there is no heir of Class I, then upon heirs being the relatives specified in Class II;

• Thirdly if there is no heir of any of the classes, then upon the agnates of the deceased; (one person is said to be agnate of another if the two are related by blood or adoption wholly through males) and;

• Lastly, if there is no agnate, then upon the cognates of the deceased. (One person is said to be a cognate of another if the two are related by blood or adoption but not wholly through male).

CLASS 1 HEIRS:

1. Son

2. Daughter

3. Widow

4. Mother

5. Son of a predeceased son

6. Daughter of predeceased son

7. Widow of predeceased son

8. Son of predeceased daughter

9. Daughter of predeceased daughter

10. Son of predeceased so of predeceased son

11. Daughter of predeceased so of predeceased son

12. Widow of predeceased son of a predeceased son

General Rules of Succession – FEMALE HINDU

The property of a female Hindu dying intestate shall devolve:

• firstly, upon the sons and daughters (including the children of any predeceased son or daughter) and the husband;

• secondly upon the heirs of the husband;

• thirdly, upon the mother and father;

• fourthly, upon the heirs of the father; and;

• lastly, upon the heirs of the mother

However, if any property is inherited by a female Hindu from her father or mother it will devolve in the absence of any son or daughter of the deceased (including the children of any predeceased son or daughter) not upon the heirs referred to above but upon the heirs of the father; and any property inherited by a female Hindu from her husband or from her father in law will devolve, in the absence of any son or daughter of the deceased (including the children of any predeceased son or daughter) not upon their referred to above, but upon the heirs of the husband.

WILLS

Will means a legal declaration of the intention of a testator with respect to his property which he desires to be carried into effect after his death. It can be revoked or altered by the maker of it at any time he is competent to dispose of his property.

A will made by a Hindu, Buddhist, Sikh or Jain is governed by the provisions of the Indian Succession Act, 1925. However Muslims are not governed by the Indian Succession Act, 1925 and they can dispose their property according to Muslim Law.

Origin of Will in India

The origin of Will in India is shrouded in obscurity. There is no Sanskrit text dealing with this subject. However a Sanskrit term - `Marana Shasanam' is mentioned in earlier writings. The reason for the scarcity of the Will in those days could be attributed to the Hindu orthodox view that the children's rights cannot be debated or questioned. Decision of the Privy Council (during the British regime) which was the ultimate court then laid down as law whatever the "Dharmasastran" had empowered - `that a man may give whatever remains after a certain amount of property is retained for the maintenance of the family'.

Later different states laid down laws concerning the disposition of property. The power of a Hindu to Will away his property was first recognised in Bengal. The decision of the High Court of Tamil Nadu confirmed the view that a person could will his or her property, provided it is not ancestral. Laws relating to the writing of a Will were finally passed in 1925 - with the passing of the Indian Succession Act which applies to all wills made by a Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain etc.

Competency to make will

• Every person who is of sound mind and is not a minor can make a will.

• Any married woman can make a will of any property which she could alienate during her life time.

• Persons who are deaf or dumb or blind can make a will provided they are able to know what they do by it.

• A person who is ordinarily insane may make a will during an interval in which he is of sound mind.

• No person can make a will while he is in such a state of mind, whether arising from intoxication or from illness or from any other cause, that he does not know what he is doing.

Execution of Will

• The testator (person making the will) should sign or fix his mark to the will or it should be signed by some other person in his presence and by his direction.

• The signature or mark of the testator or the signature of the person signing should appear clearly and should be legible. It should appear in the manner that is appropriate and makes the will legal.

• The will should be attested by two or more witnesses, each of whom has seen the testator sign or affix his mark to the will or has seen other person sign the will, in the presence and by the direction of the testator, or has received from the testator.

• Each of the witnesses should sign the will in the presence of the testator, but it is not necessary that more than one witness be present at the same time, and no particular form of attestation is necessary.

Kinds of Wills

Conditional Will: This is a Will made so as to take effect only on a contingency. For example - the operation of the document may be postponed till after the death of the testator’s wife.

Joint Will: Two or more persons may make a joint Will. It will take effect as if each has properly executed a Will as regards his own property. If a Will is joint and is intended to take effect after the death of both, it will not be admitted to probate during the lifetime of either.

Mutual Will: A Will is mutual when two testators confer on each other reciprocal benefits as by either of them constituting the other his legatee, the is to say, when the executants fill the roles of both the testator and legatee towards each other. Mutual Wills are also called Reciprocal Wills.

Holograph Will: A holograph is a Will entirely in the handwriting of the testator. Naturally there is a greater guarantee of genuineness attached to such a Will. But in order to be valid it must also satisfy all the statutory requirements.

Concurrent Wills: The general rule is that a man can leave only one will at the time of his death. But for sake of convenience a testator may dispose off some properties. e.g., those in one country by one Will and those in another country by another Will. They may be treated as wholly independent of each other, unless there is any inter-connection or the incorporation of one in the other. Such Wills are called concurrent wills.

Duplicate Will: A testator, for the sake of safety, may make a will in duplicate, one to be kept by him and the other deposited in some safe custody with a bank, executor or trustee. Each copy must be duly signed and attested in order to be valid. A Valid revocation of the original would affect a valid revocation of the duplicate also.

Onerous Will: This is a Will, which imposes an obligation on the legatee that he gets nothing until he accepts it completely.

Registration of Will

A will need not be registered compulsorily but if so desired it may be registered by the testator during his lifetime. Will may be deposited with the registering authority under Sec.42 of the Indian Registration Act, 1908. A Will or Codicil is not required to be stamped at all.

Wording of a Will

Sec.74 of the Indian Succession Act, 1925 lays down that the use of technical words or terms of art is not necessary in a will but the wording should be such as to clearly indicate the intention of the testator. A will must be construed as a whole to give effect to the manifest intention of the testator; Nathu v. Debi Singh, AIR 1966 Punj 226.

Codicil

Codicil is an instrument made in relation to a Will and explaining, altering or adding to its disposition. It shall be deemed to form part of a Will. (Sec.2(b) of the Indian Succession Act, 1925)

If the Testator wants to change the names of the Executors by adding some other names, in that case this could be done by making a Codicil in addition to the Will, as there may not be other changes required to be made in the main text of the Will.

If the Testator wants to change certain bequests by adding to the names of the legatees or subtracting some of them in case some Beneficiaries are dead and the names are required to be removed, all these can be done by making a Codicil. The Codicil must be in writing. It must be signed by the Testator and attested by two Witnesses.

Revocation of Will

A Will may be revoked at any time before the death of the testator but a will executed by two persons jointly cannot be revoked after the death of any one of them, if the survivor has given effect to the directions of the deceased testator. In case of two Wills, the latter one will prevail; Badari Basamma v. Kandrikeri, AIR 1984 NOC 237 (Kant).

In case of revocation, the testator should give it in writing that he has made certain changes or has revoked the will. It must be signed by the testator and attested by two or more witnesses. There should be a clause stating that the present will is the last will of the testator and any will made prior to this would stand revoked. The testator cannot revoke the will by just striking it off or scratching it. He must sign it and have it attested by at least two witnesses.

Probate of Will

On the death of the testator, an executor of the will or an heir of the deceased testator can apply for probate. The court will ask the other heirs of the deceased if they have any objections to the will. If there are no objections, the court will grant probate. A probate is a copy of a will, certified by the court. A probate is to be treated as conclusive evidence of the genuineness of a will.

In case any objections are raised by any of the heirs, a citation has to be served, calling upon them to consent. This has to be displayed prominently in the court. Thereafter, if no objection is received, the probate will be granted. It is only after this that the will comes into effect.

Though executors derive their title from the Will and not the probate, the probate is still the only proper evidence of the executor's appointment. The grant of probate to the executor does not confer upon him any title to the property which the testator himself had no right to dispose off, but only perfects the representatives title of the executor to the property, which did belong to the testator and over which he had a disposing power.

WILLS UNDER MUSLIM LAW

Under Muslim Law, every adult Muslim of sound mind can make a will. A minor or a lunatic is not competent to execute a will. Though under Muslim Law,a person gets the majority at the age of 15 years, but in India, the case of will is governed by the Indian Majority Act according to which the minority terminates at the age of 18 years, but if the guardian has been appointed by the Court for the minor, the minority will terminate at the age of 21 years. The legatee can be any person capable of holding property and bequest can be made to non-Muslim, institution, and charitable purposes. A bequest can be made to an unborn person and a will in favour of a child who is born within six months of the date of making the will can be a legatee. But according to Shia Law, a bequest to a child in the womb is valid, even if the child is in the longest period of gestation i.e., ten lunar months.

The property bequeathed must be capable of being transferred and the testator should be the owner of the said property. The property bequeathed should be in existence at the time of death of the testator, even if it was not in existence at the time of execution of the will. A Muslim cannot bequest his property in favour of his own heir, unless the other heirs consent to the bequest after the death of the testator. The person should be legal heir at the time of the death of the testator. However, under Shia Law, a testator may bequest in favour of his heir so long as it does not exceed one third of his estate and such bequest is valid even without the consent of other heirs. The consent can be given before or after the death of the testator. But if the entire estate is bequeathed to one heir excluding other heirs entirely from inheritance, the bequest will be void in its entirety. According to Sunni Law, the consent by the heirs should be given after the death of the testator and the consent given during the lifetime of the testator is of no legal effect. Under Shia Law, the consent by the heirs should be free and a consent given under undue influence fraud, coercion or misrepresentation is no consent and the person who has given such consent is not bound by such consent. The consent by the heirs can be given either expressly or impliedly. If the heirs attest the will and acquiesce in the legatee taking possession of the property bequeathed, this is considered as sufficient consent. If the heirs do not question the will for a very long time and the legatees take and enjoy the property, the conduct of heirs will amount to consent. If some heirs give their consent, the shares of the consenting heirs will be bound and the legacy in excess is payable out of the shares of the consenting heirs. When the heir gives his consent to the bequest, he cannot rescind it later on.

Principle of rateable abatement in case heirs does not give consent Under Hanafi Law, if a Mohammedan bequests more than one/third of the property and the heirs does not consent to the same, the shares are reduced proportionately to bring it down to one/third. Bequests for pious purposes have no precedence over secular purposes, and are decreased proportionately.

Bequests for pious purposes are classified into three categories:

(i) Bequest for faraiz i.e. purposes expressly ordained in the Koran viz. hajj, zakat and expiation for prayers missed by a Muslim.

(ii) Bequest for waji-bait i.e. purposes not expressly ordained in the Koran, but which are proper viz. charity given for breaking rozas.

(iii) Bequest for nawafali i.e. purposes-deemed pious by the testator, viz. bequest for constructing a mosque, inn for travellers or bequest to poor. The bequests of the first category take precedence over bequests of the second and the third category and bequests of the second category take precedence over those of the third.

Under Shia Law, the principle of rateable abatement is not applicable and the bequests made prior in date take priority over those later in date. But if the bequest is made by the same will, the latter bequest would be a revocation of an earlier bequest.

Oral or written Will

Under Muslim law, a will may be made either orally or in writing and though in writing, it does not require to be signed or attested. No particular form is necessary for making a will, if the intention of the testator is sufficiently ascertained. Though oral will is possible, the burden to establish an oral will is very heavy and the will should be proved by the person who asserts it with utmost precision and with every circumstance considering time and place. But if the marriage of a Muslim has been held under Special Marriage Act, 1954, the provisions of Indian Succession Act, 1925 will be applicable and he cannot execute a will under Muslim law.

Revocation of will by a Muslim

The testator can revoke his will at any time either expressly or impliedly. The express revocation may be either oral or in writing. The will can be revoked impliedly by testator transferring or destroying completely altering the subject matter of the will or by giving the same property to someone else by another will.

About the Author

Rajkumar S. Adukia

B. Com (Hons.), FCA, ACS, AICWA, LL.B, M.B.A, Dip IFRS (UK), Dip LL & LW

Senior Partner, Adukia & Associates, Chartered Accountants

Meridien Apts, Bldg 1, Office no. 3 to 6

Veera Desai Road, Andheri (West)

Mumbai 400 058

Email rajkumarfca@gmail.com

Join LAWyersClubIndia's network for daily News Updates, Judgment Summaries, Articles, Forum Threads, Online Law Courses, and MUCH MORE!!"

Tags :Family Law